- Home

- Gary Paulsen

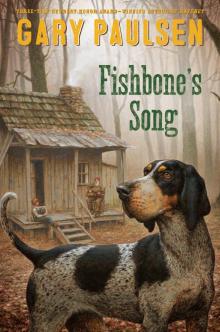

Fishbone's Song

Fishbone's Song Read online

This book is dedicated,

with great love and enormous respect,

to my friend and editor David Gale.

We worked together years ago and now again. . . .

1

* * *

Timewhen

Could have been April when this started, this whole business about Fishbone’s song, which I ’spose could be called my song just as well. Thing is, I know where it went and sort of how long it lasted.

Or not, maybe it wasn’t really April, at least not the way time works here in the woods where we live next to Caddo Creek, just where it spills across three big rocks to make something almost like the homemade music I try to do on the old small guitar I found in the back of the caved-in ’shine shack.

I only know what the time of the day it is so that when Fishbone says:

“It’s the time when the willow bark slips enough to cut a thumb’s worth and make a high whistle for to blow. . . .” Then I know soon the creek will be swollen from the runoff out of what Fishbone calls “. . . . the long mountains,” which I’ve never seen but will someday. And then there will be the little chub fish with the rainbow on their side to net and cut in slits to smoke. And the mushrooms will come soon after the chubs run, mushrooms hiding in the grass like tiny Christmas trees until you see one and then they all seem to jump out at you, and after that to cut and dry them on a slab board in hot sun . . .

When he says that, when he says “time when,” it always comes out as one word: “timewhen.” Which he says a lot, all the time, about a lot of things. He’s old. Very old. So old he can’t really be figured in years or regular time and sometimes he’ll just say “timewhen” and not follow it up with what he was thinking about. Instead he’ll look off at a cloud even if there aren’t any clouds in the sky, and smile at some little or big thing only he knows, only he can remember. It might be something as small as a hummingbird hovering on a wild raspberry flower or as big as a war. Same smile. And he might tell you then if you ask him and he might not until later, maybe a year later, when he’s sitting on the porch smoothed with ’shine made by the man I’ve never talked to who brings the clear alcohol in the middle of a night in half-gallon canning jars. Fishbone’s old foot will tap his old work boot in a kind of tap shuffle tap, and he’ll look off into the place he was then, back then, and he’ll tell you in soft words that run together like new honey about what it was; hummingbird or war. Same voice. Same sound.

Nobody knows why they call him Fishbone or even when it might have got started as a name for him. He once said it was because he got a fishbone stuck in his throat and two doctors had to hold him in a half-broken-down wooden chair full of splinters and knots, one holding his mouth open while the second one, who was younger, dug down in his throat with a rusty pair of horseshoe tongs. They pulled out the bone, which came from a big old yellow channel catfish caught off a mudbank, and all he had to ease the pain was two swallows of clear corn moonshine . . .

All the parts of the story tight and told like they were true and they might have been, probably were, the true story. Except that maybe a week later he would tell it different and say that it was when he was fishing for crawfish and had no small hook and had to make one from the backbone of an ugly gar fish he killed in the shallows with a piece of driftwood he used for a club.

And it was not until later, on a still summer night, sitting on the porch listening to the whine of night bugs hitting the water in the dog dish where the moon had come down to sit, that you would find that both stories were true or were thought true . . .

Thoughttrue.

Like timewhen.

All the same, all the same time or place or something happening. No difference in those things because the main part was that it was his name.

Fishbone.

Stories about how I came to be with Fishbone, by him, of him, family to him—all true, all different. All told by the stove in cold times or on the porch on summer evenings while he was sipping ’shine from an old jelly jar or doing what he called “hogging around” in the garden.

First story I heard I was a baby still in birth blood in a wooden beer crate down where the creek crossed under the county firebreak trail. The trail was right on the edge of being a road that sometimes people would use to come into the dark woods, the old woods, for their own reasons, sometimes dark reasons.

Ugly, he said.

Ugly and wrinkled like a baby pink rat and squalling like a hog stuck in a fence. He found me from the noise I made just before a bear got me. Fishbone was working the creek for chubs or maybe a turtle to eat, and he yelled at the bear that was dragging the crate away, and it dropped the crate and ran off, and Fishbone took the crate and me home with him. Was the crate that was in his mind first, he said; it had iron corners bracing good clear pine wood slats that would work just near perfect in back of the stove to hold wood. When he got to it and saw me, saw what it was that had been squalling and screaming, he just took it all home, crate, baby, and all. Thought, he said, that the baby wouldn’t last long anyway and he’d bury it when it passed and still have the crate for the back of the stove. Like any other thing that came drifting down the creek that he could find to use.

I was, he said, like Moses in the Bulrushes, drifting down a river . . .

Which sounded made up until I learned to read and found the story in a big leather book. But I still don’t know what a bulrush is except it’s something to do with water and has nothing to do with bulls. Or me, for all that.

Could have been a tale like the story about his name, about the stuck bone or the small gar fish hook. Especially when you heard the other stories about how he had a second or third or fourth cousin who had a daughter who found herself with a baby she didn’t much want or know how to raise. It—I, that is—went from cousin to sister to cousin, until finally I came down to being with Fishbone who was already old, so very old, and he didn’t have anything to do for the rest of his life except live in a tumbledown cracky-shack in the woods, and so I had a home.

Third story was I was left with a note in a cardboard box on a church step. The God man who found me there knew somebody from the family that took in kids, and they knew somebody else who could take a kid, but none of them could have any more kids to care for. I wound up with a state woman who looked for blood family and that brought her, finally, to Fishbone, and since we come from some same kind of family blood, I was given to him.

To raise.

And other stories about being found where fairy families had left me under the side of a night-glowing old stump in a shallow hole. Fishbone was looped on ’shine and since he could feel and see things of mystery when he was on ’shine, he saw me there, in the glow from the stump. He took me home thinking I was witched and could see things ahead and maybe bring him good luck, like a piece of clear rock candy or a double yolk egg when you crack it in the pan. If the yolks don’t break before they fry . . .

All mixed stories and seemed to be made up except:

Except.

In back of the stove is the wooden beer crate with good pine slat sides and steel-braced corners and some old stains that might have been left by my birth blood.

And.

When they come to get me and made me go to school for a year and a little more until they knew I could never fit in, had some big words about how I could never fit in and brought me back to live with Fishbone, with my family, but in the meantime taught me to read. Right there, right then, I saw an old letter from the state said they would send a little check to Fishbone once a month to raise me in a “goodly manner.”

And.

When I came on being maybe ten or eleven or twelve years in the world, I was hunting of an evening for either a fox squirrel or a grouse because Fi

shbone had a feeling he wanted to eat one or the other and I came into a gulley and there it was . . .

A stump, a fairy stump where I could have been put down in a small hole as a new baby by the woods people, the night woods people, their stump, glowing blue-green in the new dark so pretty it almost had a sound, a blue-green sound I tried to make on the guitar as part of his song, Fishbone’s song. And you take that along with finding that I sometimes see things ahead—like I can know, absolutely know for certain if a squirrel is on the other side of a tree even without seeing him. Know enough to make the sound, the “chukker” sound that will bring his head around the side for the one clear shot so you don’t ruin any meat with the bullet and you kill him with the brain shot so very sudden the death smell, the gut smell, won’t taint the stew. All without seeing the squirrel first, just knowing it’s there.

So then true, all the stories about how I came to be with Fishbone were true, or could be true, thought true.

Thoughttrue.

Or maybe none of them.

But there was the wood box, and the letter from the state, and the glowing stump, and me, there I was, and Fishbone, and the woods, and the creek. So who can say which is real or not completely quite?

And Fishbone’s song, his first song, with a hum at first and then the words all coming in an up-and-down roll to match the old boot tapping and sliding on the porch boards to make time, and a soft shuffle sound like the boot was dancing and drumming at the same time.

First Song: Witching Boy

Witching boy,

in the night,

in the night.

Witching boy,

brings the light,

brings the light.

For everyone to see,

and know,

Witching boy,

brings the glow,

of life.

Shine on, shine on, Witching boy.

2

* * *

Newtime

No memories of living at first . . .

Just clouds of pictures and thoughts that might have been, probably were, like music you can almost hear and think you hear, but it’s not almost really there. Fuzzy. Until the state came and took me when I was small and then taught me to read, I didn’t have anything but picture memories.

They worked, the way Fishbone’s stories—his songs—worked. I would see something, like a red berry bush, but I didn’t know colors, how to say or think colors, and Fishbone would say things that worked, but only for someone who knew some things.

I didn’t know some things. I didn’t know how anything was said. He’d say something was the same color as the bottom stripe on the side of a creek chub, or that a panther scream was a caterwaul coming on like two men fighting with barbwire whips and hard words . . .

I didn’t know yellow-blue, which was the bottom stripe on a creek chub, or that what panther-cats did when they got to talking was really to give out a screech that made the hair come up on the back of your neck. And on that was the fact that I’m old now, either ten or eleven or twelve, maybe thirteen summers, and I have never seen men fight each other, especially with barbwire whips and hard words.

Haven’t seen any other men, period, as far as that goes, except for once a month when the man from the state comes to check on things and brings a big box of what Fishbone calls “fixins” to make food—flour, bacon, salt, sugar, coffee, now and then a jar of pickled beets or small cucumber pickles some church group puts in the box because, Fishbone says, it makes them feel like good people. I like the good people pickles, kind of sweet and sour at the same time, but don’t like the beets because they make you pee red and I don’t like that. To pee red. Fishbone says for me to eat a slice a day just the same because he says it has iron in it, but I can’t see any trace of iron in the beets or the pickling juice. Plus I had a small magnet I found in a box of junk in the attic, or sort of an attic, and it didn’t stick to a beet slice and so that was that.

No iron.

Oh, one other man we see, or sort of see now and then, is the man that comes sometimes on a dark night to leave a jar or two of moonshine. I stayed up one night and got a look at him. Fishbone leaves a few small bills or silver change from what he calls his war money because he fought in a place called Korea and got shot some. That’s how he says it: “I got shot some, there in a place called Korea, and they’ve sent me money since.” The man with the box of fixins brings the money once a month when he comes to check on us. Or on me, I think. And then Fishbone leaves a little money on the side of the porch in an empty ’shine jar when the other man comes in the night with new ’shine.

He looks just about like Fishbone, far as I could tell in the dark: old, with a hacked-down beard. Except he might move a little easier than Fishbone, who moves slow, and now and then has a left limp. I asked him once if the limp was because he got shot some in the place called Korea, but he just looked off at the sky and had that smile. Soft smile. Like he was remembering something good, which didn’t make sense if you’re thinking about getting shot some.

Only one time he talked about it was when he drank over half a jar of ’shine sitting in the rocker on the porch and told the story-song about the first time he had what he called deep love, book love, magazine love, going to marry her forever love, for sure and true love. But. The army come and took him to go to the place called Korea, where he said he liked to froze to death, was never so cold. So cold that when he got shot, some of the blood froze on the way out and plugged the holes in him so he didn’t bleed out and kept him alive just long enough. Just long enough for them to throw him across the hood of a jeep bouncing down a frozen road, tied down with two other men who were already dead and frozen stiff. Heard the bullets hitting the frozen bodies. Just long enough to get him to a doctor who fixed the holes in him. Just long enough for him to get back across the ocean in a plane, and find his first deep love that he thought would last forever had up and taken to a new man who hadn’t gotten shot some in the place called Korea.

His story-songs were like going up a stairway or a ladder where at the ground there was just a touch of something you knew would be good, and if you waited and climbed it, there would be something good at the top.

His best story-songs, the ones where he went in his thinking to the small smiles and looking off into the clouds, came when he sat in the chair and drank half a jar of ’shine. Didn’t last long. Like burning a candle at the top of that ladder. Get up there, get the good story, then the ’shine would be too much, and the candle would burn out, and he would get quiet again, looking off into private places until his old eyes closed on the memories and he would sleep.

Sit there and snore, Old Blue dog next to the chair sleeping with him, sleeping like he’d been poured onto and into the porch, snoring the same exact sound as Fishbone. Like he’d been drinking ’shine with Fishbone. Thing is, he wasn’t old. Had three dogs since I came, or maybe four, coming on five, all flop-eared, drooling hounds so full of love they’d come up and put their head under your hand to feel like they were being petted, move their head back and forth for the feeling.

Every one named Old Blue. Fishbone said all hounds had to be named that. Old Blue. Because of a song that had a line that said, “Old Blue, you good dog, you.” Named right off, as soon as they came to us—and that’s what happened; they just came to us. They’d show up all covered with mud and tick and fly bites and move in, and as soon as they were there, they’d get next to Fishbone and stick there like they’d been there all their lives, act all old and tired, and sleep next to Fishbone and the rocker unless I went to go hunting. Then they’d jump up and hit out of the front of the cabin like they were on fire.

They were good to go with if you watched them, watched and listened to them and knew how they acted, and that would tell you things. Where an animal might be, and what kind of animal it was; one sound if they saw a squirrel, another sound—almost like a bell—if they treed a coon or bear, and just howled murder if they saw and chase

d a deer.

I asked Fishbone once where they came from when they just showed up, and he said God sent them, said God made them in the forest out of spare parts of other animals, leftovers, and that’s why they were so floppy and loose skinned, and they roamed the woods until they saw a place they liked and they moved in and sat down. Of course I knew that people used them, hunted with them, and that sometimes they ran and got so far they didn’t come back; that’s how the people lost them. They’d start to run a deer and go so far and fast they wound up belonging to us.

Or maybe I should say they came and laid down. Next to the rocker, sleeping when Fishbone sipped ’shine and did his word-songs, and they went to getting fed scraps and cooked guts from fish and animals I hunted, which we mixed with boiled rice. Went to getting fed and petted. Fishbone said it was the onliest true love there is in the world, the way a dog loved, unless you found the right woman, which he thought he did twice. But was wrong. Or he said some had the true love of Jesus, but he wasn’t one of them, though he thought maybe that was as good as the dogs’ love. Clean, he said, clear and clean and no chains holding. I sat by a tree for a time one afternoon in the sun with Old Blue number three with his head in my lap and wondered if I had the true love of Jesus but no feeling came, and I thought maybe you had to be older, or know more. Maybe later, I figured, when Jesus got to know me better or I got to know him. Fishbone said He was everywhere and that if I listened to him when he sat in the rocker and talked and learned about things, it all might come to me. Or might not. He said it had not come to him, the true love, either with a woman or Jesus, but it was still there, out there, for the lucky ones. In the meantime he said the love from a dog would help me to understand about it.

Love.

I’m not sure when I started to learn things from Fishbone. Might have been right away when I came to him, however that happened. I can’t remember much from the first times except that when I was, I think, three or four, he taught me how to pee off the porch on the downwind side so it wouldn’t splatter back on my legs, and to use the outhouse and magazine paper to wipe, because if I did it again in the yard, the dog would eat it and lick my mouth afterward and give me worms in the butt. I don’t know if all that is just perfectly true, but every dog we’ve had has licked my mouth if he caught me off guard, so I figured it wasn’t worth taking a chance. I don’t want worms in my butt.

Hatchet br-1

Hatchet br-1 Gone to the Woods

Gone to the Woods How to Train Your Dad

How to Train Your Dad The Haymeadow

The Haymeadow Amos Binder, Secret Agent

Amos Binder, Secret Agent The River br-2

The River br-2 Amos Gets Married

Amos Gets Married Father Water, Mother Woods

Father Water, Mother Woods Dunc and the Scam Artists

Dunc and the Scam Artists Dogsong

Dogsong Alida's Song

Alida's Song The Wild Culpepper Cruise

The Wild Culpepper Cruise Brian's Hunt

Brian's Hunt Woods Runner

Woods Runner Dunc and Amos on Thin Ice

Dunc and Amos on Thin Ice The Treasure of El Patron

The Treasure of El Patron Dunc Breaks the Record

Dunc Breaks the Record Harris and Me

Harris and Me How Angel Peterson Got His Name

How Angel Peterson Got His Name My Life in Dog Years

My Life in Dog Years Tucket's Travels

Tucket's Travels Canyons

Canyons Dunc and the Flaming Ghost

Dunc and the Flaming Ghost The Schernoff Discoveries

The Schernoff Discoveries The Winter Room

The Winter Room Road Trip

Road Trip Masters of Disaster

Masters of Disaster Flat Broke

Flat Broke Dunc and Amos Hit the Big Top

Dunc and Amos Hit the Big Top Time Benders

Time Benders Caught by the Sea

Caught by the Sea Dancing Carl

Dancing Carl The Seventh Crystal

The Seventh Crystal The Boy Who Owned the School

The Boy Who Owned the School Six Kids and a Stuffed Cat

Six Kids and a Stuffed Cat Super Amos

Super Amos Dunc and the Greased Sticks of Doom

Dunc and the Greased Sticks of Doom Amos and the Chameleon Caper

Amos and the Chameleon Caper Fishbone's Song

Fishbone's Song Curse of the Ruins

Curse of the Ruins Brian's Return br-4

Brian's Return br-4 Molly McGinty Has a Really Good Day

Molly McGinty Has a Really Good Day Captive!

Captive! Culpepper's Cannon

Culpepper's Cannon The Car

The Car Puppies, Dogs, and Blue Northers

Puppies, Dogs, and Blue Northers Coach Amos

Coach Amos Mudshark

Mudshark The White Fox Chronicles

The White Fox Chronicles Dunc and Amos Meet the Slasher

Dunc and Amos Meet the Slasher Field Trip

Field Trip The Cookcamp

The Cookcamp Crush

Crush Lawn Boy Returns

Lawn Boy Returns Liar, Liar k-1

Liar, Liar k-1 Thunder Valley

Thunder Valley The Tent

The Tent The Beet Fields

The Beet Fields The Creature of Black Water Lake

The Creature of Black Water Lake Rodomonte's Revenge

Rodomonte's Revenge Guts

Guts This Side of Wild

This Side of Wild The Rifle

The Rifle The Time Hackers

The Time Hackers Amos Goes Bananas

Amos Goes Bananas The Amazing Life of Birds

The Amazing Life of Birds Dunc's Undercover Christmas

Dunc's Undercover Christmas Hook 'Em Snotty

Hook 'Em Snotty Amos and the Vampire

Amos and the Vampire Danger on Midnight River

Danger on Midnight River Grizzly

Grizzly The Legend of Red Horse Cavern

The Legend of Red Horse Cavern The Transall Saga

The Transall Saga Lawn Boy

Lawn Boy The Case of Dunc's Doll

The Case of Dunc's Doll A Christmas Sonata

A Christmas Sonata Brian's Winter br-3

Brian's Winter br-3 Vote

Vote The Rock Jockeys

The Rock Jockeys Nightjohn

Nightjohn Escape from Fire Mountain

Escape from Fire Mountain The Case of the Dirty Bird

The Case of the Dirty Bird Brian's Winter

Brian's Winter Amos's Killer Concert Caper

Amos's Killer Concert Caper Amos Gets Famous

Amos Gets Famous Brian's Return

Brian's Return Dunc and the Haunted Castle

Dunc and the Haunted Castle The Monument

The Monument Dunc and Amos Go to the Dogs

Dunc and Amos Go to the Dogs World of Adventure Trio

World of Adventure Trio Amos and the Alien

Amos and the Alien Cowpokes and Desperadoes

Cowpokes and Desperadoes Dunc and Amos and the Red Tattoos

Dunc and Amos and the Red Tattoos Dunc's Dump

Dunc's Dump Skydive

Skydive Prince Amos

Prince Amos The Gorgon Slayer

The Gorgon Slayer Dunc's Halloween

Dunc's Halloween Flight of the Hawk

Flight of the Hawk Dunc Gets Tweaked

Dunc Gets Tweaked Brian's Hunt br-5

Brian's Hunt br-5 The Night the White Deer Died

The Night the White Deer Died